|

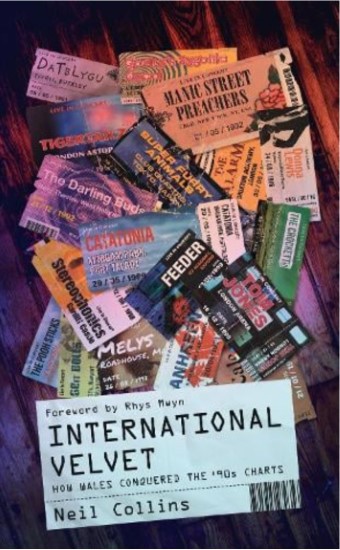

Neil Collins

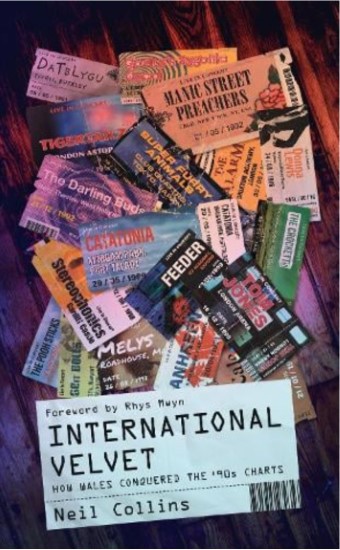

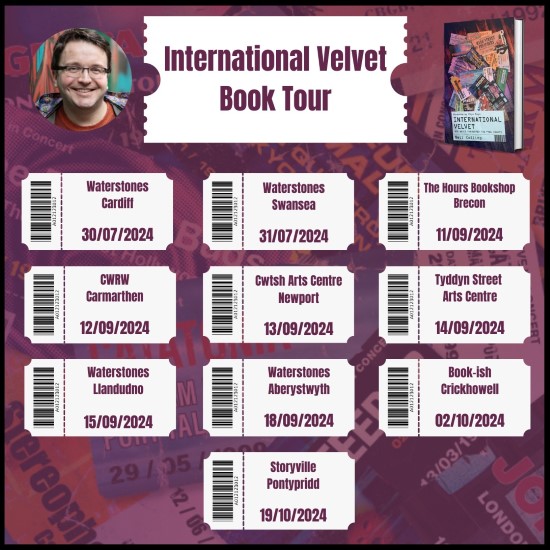

On the publication of his book

International Velvet

Interview by Tom Emlyn

Neil Collins' new book 'International Velvet: How Wales Conquered

The '90s Charts' is a brilliant and well-researched analysis of a fascinating

period in Welsh music history. A time when Wales shook off its backwater

image and made its mark on the pop scene, making the current rich and

varied scene in Wales possible, both in English and Cymraeg. Collins

leaves no stone unturned, addressing all the most important bands active

at the time as well as unearthing some underrated gems and also analysing

the use of the sometimes derided 'Cool Cymru' moniker. I caught up with

Neil to have a chat about the book.

Tom: First of all, I was just wondering how the book actually

came about - what was the original inspiration, how did it all fall

into place?

Neil: It came about in lockdown, three years ago. August 2021, I had

an email from the University of Wales Press, and they were about to

celebratrrre their 100th anniversary, so they were launching a new non-fiction

print called Calon (which means 'heart' in Welsh). They had listened

to the Welsh Music Podcast , which I co-host with my friend James, and

they wanted to know whether we were up for writing a history of welsh

music, really. I suppose in one volume it's quite exhuastive, trying

to write a history of Welsh music. What genres do you include? How far

do you go back - back to the 50s, 60s? We came to the conclusion that

by doing an entire exhaustive history of Welsh music, you're only superficially

covering artists, you're not going into any depth, cause there's so

much to include. So we thought the 90s - there's such a nostalgia for

the 90s now, especially people my age, nearing 40 now. Not just Cool

Cymru, Britpop as well. Whether you like it or not, it's still quite

an interesting period to look into and revisit. I bumped into Huw Stephens

the other day, he's just released his book Wales - 100 Records. He said

that part of the reason he wrote the book was that he was sad that it

never existed before. So although the Cool Cymru era was covered quite

extensively in the press back in the day, there's never really been

a book that's gone into depth on it. There's been individual books on

the Manics and Catatonia, the Furries, Stereophonics. But 1999 seems

the peak of the whole period for me. You've got no 1 albums for Catatonia,

and Stereophonics have got huge gigs at Morfa Stadium and Margam Park.

25 years on from the peak of that whole scene seems quite a good time

to look back - obviously you've got devolution and the creation of the

Welsh Assembly in 1999 as well. So it's looking back on a time when

there was a real feel-good factor in Wales; a marriage between music,

culture, sport, politics and language. So it seemed a good time to look

back.

Tom: It's a period that obviously has created where we are now in Wales,

really, hasn't it. I think you're right that it's very important time

in the history of Welsh music, so it's a great idea for a book.

Neil: It was a sort of golden era. You've got the Manics and Super Furry

Animals, who I think are real sort of generational talents. You only

get bands like that once or twice in a generation, really. You've got

solid bands like Stereophonics as well, with a commerical allure. You've

got creative and idiosyncratic bands like Gorky's Zygotic Mynci as well,

which became part of the scene. All coming about pretty much the same

time, which I think is incredible really. I think the feel-good factor

of the music definitely created a groundswell of optimism that led to

devolution, as well. I think it definitely seems like a more positive

time than now. I suppose there were still wars going on back then, like

Kosovo and so on. I think politically a more positive time. But then

I suppose Labour have come in now for the first time in fourteen years.

Hopefully - to paraphrase the song - things can only get better.

Tom: I mean, Thatcher's Britain did create a lot of music

in a very different way, as well.

Neil: Yeah, I think that is kind of in spite of Thatcherism. It was

such an interesting era to rebel against - if something's in rebellion,

it'll always produce great art. I think the Manics said, they were kind

of reluctant sons of Thatcher, really. They came from a South Wales

mining town that had been decimated following the miners' strike and

the rigid laws that Thatcher imposed. Certainly their early stuff was

real sort of fiery stuff. The thing is with the Manics, they're still

political now, but I think they can't be quite the same firebrands that

they were, that's a byproduct of being young and rebellious.

Tom: It's an inevitable product of getting older, I suppose.

Neil: The fact that the Manics have mellowed, as well - that was always

gonna happen. Can you imagine the stuff they were saying in the early

90s, with Twitter around? The stuff Richey and Nicky used to say - they'd

get cancelled in no time.

Tom: People expect much better behaviour from rockstars these days,

don't they. Have you seen what's happened to Tenacious D?

Neil: I did see Jack Black was trending earlier, what was that about?

Tom: Obviously, Trump was nearly assassinated the other day. Kyle Gass

(Tenacious D guitarist) made a poorly-judged joke about 'not missing

trump next time', while they were on tour in Australia. And the Australian

government basically threatened to deport them for inciting political

violence. So they've had to issue a public apology and the tour's had

to stop. And that's nothing, compared to some of the things the Manics

used to say. It seems like now we hold musicians to much higher moral

codes than politicans, ironically.

Neil: There was some stuff that the Manics did say that was abhorrent

really, like the Michael Stipe comment from Nicky - you just can't defend

that at all. I think with the Manics, it's often overlooked that they've

got a real dark sense of humour. Richey said 'if Wales was a museum,

it'd be full of rubble and shit' - it's one of those things where it's

like 'it's our shithole'. They're very defensive of where they're from,

so they can take the mick out of it. It's that gang mentality of where

you're from. Another was when Richey said 'we always hated Slowdive

more than Adolf Hitler'. It's that outrageous, you can't help but think

'this is clearly meant to be outrageous and tongue in cheek'. Now, there's

less nuance and you're on one side or the other. There's no grey area

now.

Tom: Culture has changed hugely since the 90s, and so

has music. It would be impossible now for music to unite so many people

in such an intensive way, as it was at that time. Everything is just

a bit more...atomised now, in its own seperate bubbles.

Neil: It's a funny one, cause social media's made the world a much smaller

place. You can put something on the net and it's across the world in

seconds. You can't quite imagine how big Oasis were back in the day

- I think they could have played Knebworth another fortnight, another

14 nights. Playing to 125,000 per night. It was something like 5% of

the UK applied for tickets to Knebworth - all on phone lines, back then.

No real mobile phones, the internet hadn't quite boomed at all. Same

as the Manic Millenium, really. That last mass gathering before the

internet has really boomed. It's quite a different experience. Certainly

when I started watching gigs, when I was 16, compared to what it is

now. Phones everywhere - people kind of watch gigs through their phones,

to an extent. I'm probably talking a bit too much about Oasis for a

Welsh interview, but they had John Squire come back for the first night

at Knebworth, and they were able to keep it quiet for the second night

as a surprise. That would never happen now.

Tom: It would be up on Twitter, instantly.

Neil: Absolutely, yeah. The Manics were always amazing at producing

their own hype and propaganda. I think the press loved them because

of that, they always produced great copy. So in a way, they'd probably

be bigger now, because the stuff they would say - they'd probably have

to temper it a bit - but on social media, they'd be huge.

Tom: Reading the book, it did make me think about how Welsh music has

changed since then. I'd argue in the last few years there's been another

boom in Welsh music. Especially since Covid, I think.

Neil: Yeah, I think there's been some brilliant labels, like Libertino,

who've done some brilliant stuff - Bandicoot, Adwaith, Keys. There's

artists like Gwenno, who's been nominated for the Mercury Prize. Skindred

have won the first MOBO for a Welsh artist. Adwaith have won two Welsh

Music Prizes. You've got Buzzard Buzzard Buzzard, who have supported

Noel Gallagher. Hana Lili, who supported Coldplay last year, and Himalayas

and Chroma who supported the Foo Fighters recently. It does seem there's

a lot more on the map. The big difference, unfortunately is the huge

gulf in units they were shifting in the 90s. It was the last era of

any mystery to a band - if you wanted to know anything about them, you

had to buy the music press and you had to buy the records. Whereas now,

certainly for grassroots level, streaming is just not sustainable at

all.

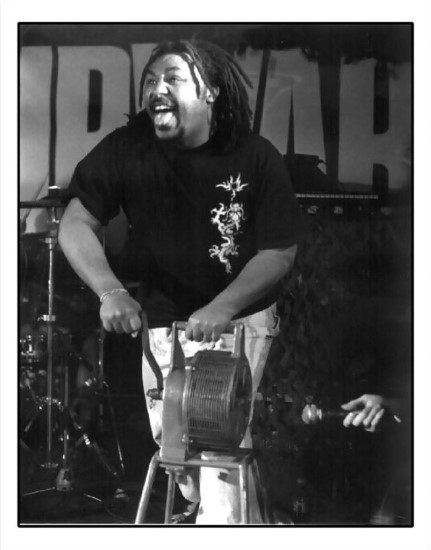

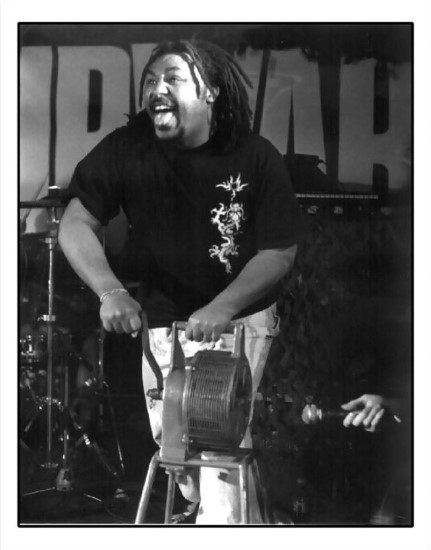

Dub War c 1994

pic Phil Rose REPEAT

Tom: It's ironic in a way, because I do think in some

ways the scene is probably better now.

Neil: I think there's less expectations, and you're free of record label

pressure, to the extent it was before, where say you were signed to

Sony and you'd have to get album two out within six months of the first

one, or get another single out and squeeze out three or four b-sides

to each single. I think it's a lot freer now - you can upload a song

and just see how it goes and find your niche via. Back in the 90s, you

couldn't make so many mistakes. Around the time of The Holy Bible -

it's considered their masterpiece, but the Manics were very close to

being dropped around that time, because it was a commerical failure,

really. Luckily they did persevere and release Everything Must Go, which

arguably is their best album alongside The Holy Bible. So it's quite

fascinating, comparing the two eras. How have you found it, as a musician

yourself, in terms of the current times?

Tom: Well I think there don't seem to be any prescribed genre labels

to the same extent. I think bands can be a lot more fluid. I'm thirty

now, so I've been playing music for quite a few years. I think especially

since Covid there's been a real creative boom, even of underground bands

that people don't necessarily know about. People seem to be supporting

each other, and because they were locked up in lockdown, I think there's

been a burst in creativity. The scene in Cardiff is really quite special

at the minute. There's a lot of great up-and-coming bands.

Neil: Yeah, I think you've hit the nail on the head there, really. I

think there has been a change - people are just thinking 'we can't lose

music again, like we lost it for two years'. There was a point where

you're thinking 'my god, is live music ever gonna come back?' And I've

certainly not taken live music for granted ever since.

Tom: You talk about the Cool Cymru label quite a lot in the book. Maybe

it's a good thing we don't need a label like that now, because it is

just Welsh music now. You argue quite a lot about the pros and cons

of the term, because some people did find it quite patronising at the

time, didn't they?

Neil: If you speak to Rhys Mwyn (Anhrefn), who's featured a lot in the

early part of the book and kindly wrote the foreword as well - considering

he's from quite a punky background, he's in favour of the term Cool

Cymru to an extent. He says if it's there to collect you all together

into a scene, and you're all selling records, you're all selling out

gigs, then go for it. He always says it's better than being Uncool Cymru.

There's always gonna be a backlash from musicians towards people inventing

these terms from the outside. There's different stories of the birth

of Cool Cymru, emerging from the Western Mail and the London Press.

I do wince a little bit with it - it's a bit like Britpop, defining

a whole scene based on its national identity. There's nothing that links

Stereophonics and Gorky's, and the Manics and Super Furries, or Feeder

and 60 Foot Dolls. They're all completely disparate bands. There's one

interview quote in the book from Nia Daniel at the National Music Archive

in Aberystwyth, she says that the 'land of song' moniker has had a bit

of a divisive reaction over the years, because that was attached to

Wales by the Victorians. So it's something that's come from the outside.

I think as a collective term, it's been more of a force for good in

Wales than Britpop has in England. The frontrunners of Britpop were

great - Oasis, Pulp, Blur, Superglass, Suede, but there's a lot of jingoism

attached to it, there's a lot of flag-waving, homophobia, misogyny,

looking back on it 30 years later. I don't think we had that in Wales

with Cool Cymru. The publishers did want me to have Cool Cymru in the

title or subtitle, but I thought, it's such a divisive thing to musicians

and fans. I thought International Velvet was a better title, cause it

says so much about that shift in confidence over the decade. At the

start of the 90s, depsite huge successes like Tom Jones, Shirley Bassey,

Shakin' Stevens - who I think was the biggest selling artist of the

80s in the UK. Bonnie Tyler was huge in America, as well. Massive-selling

artists from a commercial standpoint. For alternative music fans, I

think the London press kind of laughed at Wales. In the intro of the

book, I talk about horror stories of A&R men not coming over the

Severn Bridge. Gorwel Owen, the Furries producer, said he worked with

bands from North Wales who played on the idea they were from Liverpool.

You even had bands going over to Bristol, apparently, to get an English

postmark put on their demos so labels didn't immediately chuck it on

the rejection pile. So to go from that to, eight years later, Cerys

Matthews singing 'every day when I wake up, I thank the Lord I'm Welsh'.

Whether it's tounge in cheek or ironic, that's still a massive shift

in confidence. You'd be laughed out of town singing that in 1990.

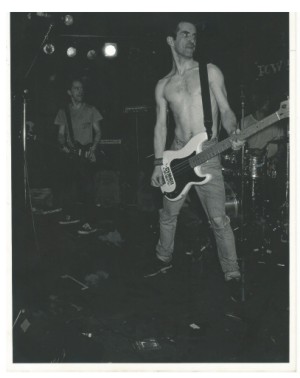

Anhrefn

early 90s, pic Phil Rose REPEAT

Tom: You write very well about all the anti-Welsh sentiment

at the time - you mention Anne Robinson from the Weakest Link, who famously

came out with some quite racist remarks. I suppose Cool Cymru did a

lot to help erase that. Attitudes to the Welsh language have improved

quite a lot in the last twenty years.

Neil: Yeah, The Alarm had a lot of flak even before the Manics. Obviously

they ventured into biligualism. The Manics, every headline in their

early days was some kind of naff pun, which if you did with any other

nationality just wouldn't be tolerated, really. Even in the mid-90's,

when Welsh bands had "proven themselves", it was still a lot

of crap puns in the headlines. You certainly don't see that now. It's

considered sort of ham-fisted and rubbish.

Tom: I was trying to think whether that's something you'd ever see these

days, that kind of naked, well, basically almost racism really.

Neil: I don't think you see the same from London journalists. You certainly

see it differently in festival stages as well, there would be bands

who were metal, jazz artists, folk artists, all on one stage just because

they were Welsh language. It's a lot more curated now, just like any

other music festivals.

Tom: I was wondering about the writing process for the book - how long

did it take, what was the research process like? Was it a massive pain,

or did you enjoy it?

Neil: It's funny really. It's both a labour of love and a long slog.

I loved the whole process of doing it. There were some days where I

thought 'is this ever gonna end', 'are people actually gonna read this?'

Basically I put all the bands - every artist mentioned in the book,

into their own seperate folder on the PC, then I would go through old

physical magazines like Forever Delayed and R.E.P.E.A.T. and places

like that, great for Manics. The website Rock's Backpages is amazing

for getting old 90s articles. I wrote it entirely non-chronologically,

in terms of whatever artist was of interest to me at that point, then

looked for linkages to make it a more coherent narrative. So I knew

that I basically wanted to start in Year Zero, I think the chapter's

called, where David R.Edwards (Datblydu) and Rhys Mwyn are trying to

rebrand Welsh culture. I knew the end-point would be Manic Millenium,

Mwng and Catatonia singing 'International Velvet'. As well as the big

hitters - the 'Big Four' you usually mention - Catatonia, Super Furries,

Stereophonics and Manics - I wanted to bring some different analysis

to those bits, cause that's well-trodden ground really. So I wanted

to get some different perspectives. For instance, I did the Manics in

conjuction with Neil Kinnock and the 1992 general election. I did a

comparison between The Holy Bible and Definitely Maybe, which were released

on the same day but are totally different albums. I wanted to introduce

bands that you don't hear of so much, great stories, like The Darling

Buds, who released Erotica on the same day as Madonna's album by the

same name, on the same label, Sony. You've got Helen Love being invited

to New York City by her hero Joey Ramone to play a gig.

Tom: I'd never heard about her meeting Bob Dylan at the

rehearsal room in New York, that was quite something.

Neil: That was pretty cool. What else - Rheinallt H.Rowlands was quite

an enigmatic figure. He was kind of like a character, a fictional story

about a stonecutter. I thought that was quite interesting.

Tom: I knew about him, because I know Alan Holmes, actually, the musician

from Bangor. His wife Zoe Skoulding was one of my lecturers in uni.

Neil: She wrote some of the lyrics for the Rheinallt H.Rowlands project.

Tom: Alan Holmes is a bit of a one-man archive of Northwalian music

in himself, really. He's got a Bandcamp page (Turqouise Coal) with loads

of albums from North Wales, most of which he's been involved with. I

think you mentioned in the book, he produced some of the early Gorky's

material and he did cover art for them as well. He's an interesting

guy. And he was in (punk band) Fflaps, as well.

Neil: I wanted to get Tigertailz in there as well, because they were

such a different beast to anything else in the book. It's the tail end

of glam metal - Wales' answer to Motley Crue. Fun to listen to - very

much that sort of Guns n'Roses, Bon Jovi mid-to-late 80's hair metal

scene. Then there's Tystion, who were releasing hip-hop in their mother

tongue. I wanted to get a lot of Welsh-language music in there, in different

locations around Wales, so it's reflective of the music of a nation.

Tom: The first chapter, covering earlier Welsh music history, in particular

I thought was really nice and well-researched. You get the whole epic

story, from the beginning to the 90's.

Neil: It's mad, really, cause the 1996-2000 chapters are literally success

after success. It's incredible really. Donna Lewis got to no.2 on the

US Billboard with 'I Love You Always Forever'. That was the highest

Welsh artist on the charts in the US since Bonnie Tyler in 1983. A huge

change in fortune, in a short space of time. Ten years ago from now

seems like two minutes ago. It's got a narrative arc to it.

Tom: I was just wondering how you see the future of Welsh music developing,

if that's not too difficult a question!

Neil: I think Welsh music is in a good place. You've got a lot of good

infrastructure like Pyst and AM, they do a lot of distribution and marketing

for Welsh artists. Bethan Elfyn's Horizons scheme, which I think is

great for giving bands opportunities to play in Rockfield and Maida

Vale, getting them to South by Southwest and things like that. The Welsh

Music Prize really illuminates on a national stage - it's become our

version of the Mercury Prize. Things like Swn and Tafwyl are getting

bigger, year on year. Tafwyl was last weekend, I think that attracted

about 40,000 over the weekend. I think it's in a healthy place. The

sad thing is that artists aren't selling in the same quantities that

they were years ago, and aren't selling at the level that their hard

work deserves. What do you think?

Tom: I agree it's in a strong place. The problems it faces are the same

problems facing the music industry in general. There's more bilingual

music around these days, bands feel freer to sing in both Welsh and

English. You talk about that in the book, how bands started to sing

in both languages, which wasn't really allowed in Welsh language music

in the 80s.

Neil: I think Welsh artists haven't got the complexes of press that's

against them based on their national identity. I think if you go back

to the 90's, it was predominately Welsh speakers that were into Welsh

language music, and there wasn't much crossover. I'm not a fluent Welsh

speaker, but I've been to Adwaith, Gwenno, Ani Glass, lots of stuff

like that. So I think it's a much healthier crossover now. There's a

great DIY scene, the younger talent coming through now knows exactly

what they want to do now in terms of uploading their own stuff and being

savvy with podcasts and Bandcamp and that sort of thing. So it's a different

world really to the 90's.

Adwaith, Swansea, Gwyl Tawe Festival , 11.6.23

Pic Rosey R*E*P*E*A*T

Tom: I was wondering what your five favourite Welsh albums

are?

Neil: I'm gonna go with a different artist for each one. In no particular

order, I would say Fuzzy Logic by the Super Furry Animals for no.5.

I love the artwork. Pete Fowler is so synonymous with the magic of Super

Furries really, but that debut album was by Brian Cannon, who was the

Britpop artist of choice. He did Definitely Maybe, a couple of Verve

albums. I just think it's got so much great stuff - 'God, Show Me Magic!'.

A perfect 2-minute song, an adrenaline rush that completely introduced

the world to their madcap genius. You've got the singles on there like

'Something 4 The Weekend'. 'Gathering Moss' is a great album track.

No 4. would be Word Gets Around by Stereophonics, I don't

think they've ever bettered that. I love that goldfish bowl (as one

of the tracks is called) style of songwriting, a tiny Welsh mining village,

which again is indicative of the change in Welsh confidence, that Cwmamman

came to national consciousness - I only lived about 30 miles away, but

I'd never heard of Cwmamman when I was young. So parochial, as well

- they weren't from Aberdare, they were from Cwmamman, although it was

only about 3 miles' difference.

No.3 would be 60 Foot Dolls' The Big Three. Amazing. The

complete sound of that, the New Seattle scene, it really captures the

adrenaline of their live gigs. Three-pieces have always got to work

harder, I think. There's less room to hide your mistakes. They really

locked in together. You've got Carl Bevan thrashing away on the drums.

You've got a really cool-looking bassist in Mike Cole, who Oasis wanted

to pinch once Guigsy left. And you've got Richard Parfitt, who's just

a great frontman. Underrated guitarist. He's got that real kitchen-sink

style songwriting to his lyrics. Like a gutter poet aspect to it.

No.2 would be International Velvet by Catatonia. It's

a really filmic front cover, iconic-looking. It's got the big singles

on it - 'Mulder and Scully', 'Road Rage', but also great album tracks

- 'Don't Need The Sunshine'. I love the way it's indicative in the change

of Welsh culture. Cerys delights in her accent, the rolled R's of 'Road

Rage', the elongated vowels of 'Mulder and Scully'. Catatonia had just

done Way Beyond Blue, which has more of a compilation feel, a mish-mash

of early singles. International Velvet hangs together as a more coherent

album.

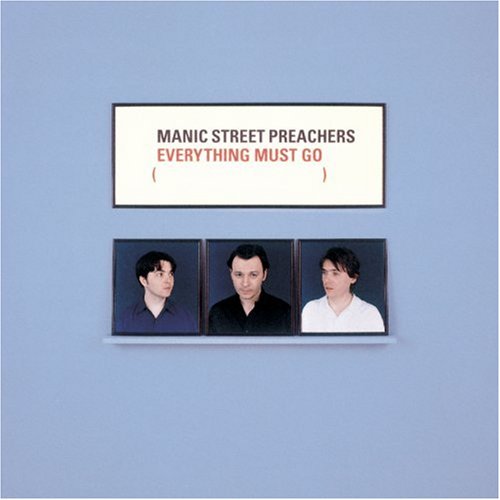

My favourite Welsh album will probably be - I know this

is sacrilege to a lot of Manics fans, but I'm gonna go with Everything

Must Go. I absolutely love The Holy Bible - it is their masterpiece,

it's their greatest artistic statement. But in terms of putting on an

album that you just want to listen to and enjoy the euphoria of it,

it's Everything Must Go. It's got 'A Design For Life' on it, which is

the most important song of their career after the disappearance of Richey

Edwards. It's got 'Everything Must Go', which distills their guilt about

carrying on as a band and whether they can be embraced again by their

fandom. You've got the amazing influence of Richey still on it with

'Kevin Carter', about the Pulitzer-Prize winning photographer who killed

himself. And then 'Australia', 'Small Black Flowers That Grow In The

Sky', another masterpiece. The album was hugely important in their future

career - it very nearly got to no.1, it won the Brit award or NME award

for Best Album Of The Year, it won an Ivor Novello with 'A Design For

Life'. It's a remarkable album. It was incredible that they could carry

on full stop after Richey's disappearance, but to come back with such

an incredible album, hats off to them.

Tom: Anything else to say about the book itself?

Neil: It's exactly the kind of book I'd like to read myself, as an obsessive

music fan. I read a lot of music books, and I think it's covered a lot

of ground, from the 60's to the 90's. Cool Cymru does still inspire

the scene of today, absolutely.

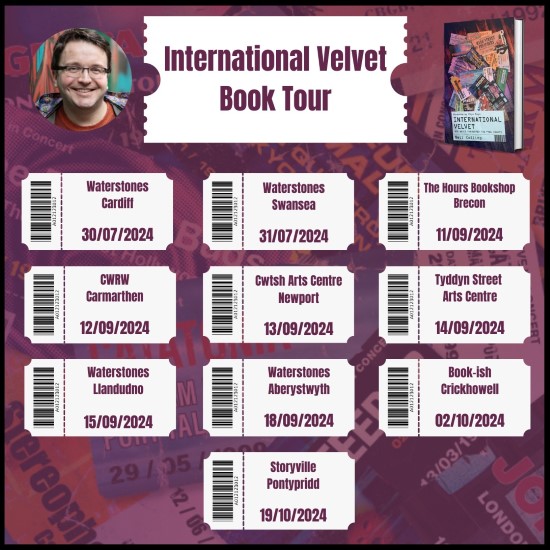

International Velvet is available from all good bookshops

from 25th July 2024.

Big thanks to Neil for his time.

*+*+*+*+*+*+*+*+*+*+*+*+*+*+

*+*+*+*+*+*+*+*+*+*+*+*+*+*+

|