|

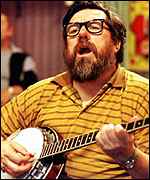

NEW LABOUR? MY ARSE! Ricky Tomlinson, star of hit comedy series The Royle Family, speaks about his jailing 30 years ago for union activity in the building industry and why we need a united socialist alternative to New Labour

|

|

Tell us about growing up in Liverpool after the Second

World War. Although we were poor-six people in a two-up, two-down house-everyone else was in the same boat. Probably we were luckier than some in that working class district of Liverpool. There was the means test. People had to pass their furniture over the back yard walls when the people from the Unemployment Assistance Board came round. If you had any decent furniture they'd make you sell it. It wasn't really struggle and hardship, because that was the norm. Like lots of working class kids, I missed out on the 11-plus exam. I have asthma and I had an attack on the morning of the exam-these tests were such a lottery. They are today as well. They used to have another exam called the 13-plus that kids were allowed to take who they thought could or should have passed at 11. I passed that and went to a technical college. I really wanted to go to a commercial college to concentrate on English. I ended up becoming an apprentice plasterer and left school. In the boom years of the 1950s there were plenty of jobs.

What was life like on the sites, and what brought you into the union?

My favourite book is The Ragged Trousered Philanthropists, which focuses on a group of building workers in Edwardian times. Nothing's changed. People are still getting killed in the building industry. There's hardly any safety work, hardly any hygiene conditions. Toilets are as rare as rocking-horse shit. The big sites that go on for years do get some semblance of organisation, so the lads can get cabins to have their meals in and stuff like that. With a bit of muscle that's what you can do. The only time you could get your mates interested in the union was when you were fighting for things like bonuses. It took the official national strike in 1972 to bring the conditions on the sites up. You were jailed for picketing at Shrewsbury during that strike.

They were absolutely terrified that the rank and file had taken control of the strike. The Tory government of the day was frightened too. Workers, through the unions, were winning important victories. That's one reason why those of us at Shrewsbury ended up in court-it was lack of support at the top of the unions. There were umpteen charges against 24 of us. But conspiracy was the main thing. If you charge someone with conspiracy, it means the court can listen to hearsay evidence. Whatever limit is on the sentence is done away with and a higher tariff is imposed. Getting sent down had a horrendous impact on us and our families. We were offered a deal on the morning of the trial. The six of us who were last to appear were told that if we pleaded guilty, we'd get fined 50 quid, the unions would pay and we'd be home by dinner time. Four wanted to take the deal, but me and Dezzie, Des Warren, said there was no way we would. I'd never been in trouble with the police, so why should I accept a stain on my character? To be fair the others said, "If you two are not, then we're not." So we all pleaded not guilty. The others got suspended sentences. I got two years and Dezzie three.

You describe prison conditions in your book. There were rats, cockroaches, silverfish. It was absolutely filthy. I was across the way from the kitchens. These cockroaches were breeding under the ovens, and it was like a black mat when I got up in the morning. Now you've got prison numbers going through the roof. You've got tens of thousands of people in prison who should be in hospital. They should be getting mental treatment. You've got the Tories lashing 'em out and calling it care in the community. And you've got so called bloody New Labour banging 'em up just to get them off the streets. It's crazy. Labour won the election in February 1974. What did that mean for

you and Des Warren? When I finally got out, no thanks to the Labour government, Dezzie was still inside and in hospital because of the way they had mistreated him. We really tried to kick up a fuss. I remember screaming from the balcony at the TUC conference, demanding that I should get a few minutes to talk about Dezzie. The chairman called the bouncers and had us kicked out. We were lucky that the TV cameras were there. They caught it all and it made national headlines. It kept Dezzie's case high profile.

How did Shrewsbury change your views about the world? At the time I wasn't wearing clothes as part of a protest at being in prison. I was in solitary confinement. He would often come into the cell and we'd talk. He'd say, "You know you really shouldn't be in here." Without using the words he was saying I was a political prisoner. The man obviously had a lot of sympathy for our cause. It was him that came into the cell one day and said, "Have you read this book?" It was The Ragged Trousered Philanthropists. He said he'd like me to have it. That was really part of the change in me. It's amazing when you read that book. Every now and then when I pick up that book to have a read it makes me go cold. Nothing has changed. People are still chained to work, still undercutting each other, taking chances with their lives to get a bit of money or to reach their target. You are on the scrap heap while working and then chucked on a bigger one after. I realised not only that there are the haves and the have-nots, but that the haves organise to make sure you don't get any of it. At the moment, I'm upset about the way we are exporting jobs to lower costs. If I wanted to export a commodity, I'd have to have a licence. If I want to throw people out of work here and employ cheap labour in worse conditions abroad, I don't need a licence at all. Look at the lives of people in those Third World countries where the call centres open up. It's appalling, all in the name of profit. Just take the World Cup. I don't think we should be buying footballs produced by child slave labour on the Indian subcontinent. We should be helping to raise people up, not push them down. These kids are working from morning to night and they are not even getting a fair deal for it. We are one of the wealthiest countries in the world and we can afford to bloody pay our way. How do you feel about today's Labour government? Blair has had his moment of glory. Things can only get better, they said-what a load of shite. I was one of those who was taken in by it back in 1997. I stayed up all night and applauded when we kicked the Tories out. I thought it would be a new dawn. But not a thing has changed. We've had this terrible war on Iraq. It's a real disappointment for me that I could not be on the demonstration on 15 February because I was working. My wife Rita was on it. What a tremendous march that was. We knew there were no weapons of mass destruction. Now Blair hardly uses those words. He's backtracking. Bush and Blair just wanted to take over the country and the oil. The resistance to Blair is the only ray of sunshine about at the moment. Arthur Scargill is a friend of mine. Come the election there'll be a little cheque for Arthur and a little cheque for the Socialist Alliance to pay for bits of printing and stuff like that. I just wish the two would get together and form a really, really strong opposition to New Labour. What do you think Labour's done for arts and culture? Instead of that, Labour are closing libraries. They are ordinary people's access to expensive books, to reading and learning. They are taking school playing fields away. Take my own Liverpool football team. I adore the club. But I do not think they should be allowed to build their new stadium in Stanley Park. I spent many happy days there as a kid and now they are going to take half of it away, depriving kids of a bit of open green space. The original plan was that their old stadium was going to be turned into a recreation area. Now that's been changed and it's going to be a shopping complex. There are loads of alternatives. It just seems to me that once again we're seeing money coming first. What I'd say to people in the movement is we have to keep our spirits up. It's a long haul. We knew it was going to be a long haul. We didn't think we'd be having to put the effort in against New Labour that we had to against the Tories. But it is a new year and a new dawn. Let's hope some leadership springs up that has got the interests of the working class at heart.

I WAS THERE Shrewsbury jailings were Tory assault on movement JIM NICHOL is now a solicitor. In 1972 he worked for Socialist Worker and helped organise the campaign to defend the Shrewsbury pickets. I GOT involved when Laurie Flynn, who was working on Socialist Worker, dragged me up to the trial in Shrewsbury. He'd gone up there week in and week out, sometimes day in and day out. I was there on the day Ricky and Des were sentenced. I was completely horrified at what I saw. But I also saw Ricky and Des speak in their own defence. That was extraordinary. It's something you don't hear often in your lifetime. Most people would never hear it in their lifetime. There was a limited campaign going on. From then on we set out to up the profile of the whole case. I became very friendly with a number of the defendants. I went to see Ricky's then wife, Marlene. She was suffering from both her husband being in prison and financially. Marlene was bringing up two kids in a place that was virtually derelict. We raised some money to keep body and soul together. We did that for Elsa, Des's wife, as well. Me and Marlene went out on speaking tours. On one occasion we spoke at six o'clock every morning to miners at a series of pits in Wales where the men had just come off shift. I went to see Ricky in prison. I started to send him Socialist Worker and he ended up with a little readers' group around him. He'd hold these discussions with some other prisoners and even a couple of officers. He came out of prison on bail in June 1974. But Ricky and Des were sent back in in October. The Shrewsbury jailings happened at a time when in many industries the unions, or rather the rank and file of the unions, were asserting themselves against the employers and Ted Heath's Tory government. There was the first national building workers' strike. That came after a series of battles on big sites such as the Barbican and Horseferry Road in London. Unofficial action and the threat of a general strike had forced the government to free the five Pentonville dockers jailed in August 1972. Shrewsbury was about the other side isolating an important strike and making an example of it. There were deep connections between the building giants-McAlpine, Taylor Woodrow and the rest-and the government. Lord McAlpine was the treasurer of the Tory party. There were also links with the judiciary and the police. The head of security at McAlpine was a former commissioner in Scotland Yard. There were even connections with some Labour MPs. McAlpine and the like wrote directly to Heath calling for prosecutions. The true conspiracy was between the large employers, the government and the police to try and break a section of workers. We are now trying to get all the documents that were held back at the time disclosed so we can pursue this miscarriage of justice. The Tories' overall plan in the early 1970s was thrown off track because, despite Shrewsbury, the government lost out to other groups of workers, most spectacularly the miners in 1974. But Shrewsbury was isolated. The trade unions let people down really badly. In the run-up to the 1974 election, and under the Labour government that came in, you got the beginnings of the argument that we should not rock the boat for "our government". That affected the key working class activists, because the main politics at the time was to look to the left union leaders, who in turn compromised with the government. The difference with the dockers was that they were highly organised at a rank and file level, and had links with stewards and convenors in other industries across London. That was lacking over Shrewsbury. The employers learnt that lesson well. Now, with the movement reviving, we should learn it too.

IN THE DOCK Ruling class conspiracy 'THE CONSPIRACY was between the home secretary, the employers and the police. It was not done with a nod and a wink. It was conceived after pressure from Tory MPs who demanded changes in picketing laws-there is your conspiracy. I am innocent of the charges and will appeal. But there will be a more important appeal made to the entire trade union movement from this moment on. Nobody here must think they can walk away from this court and forget what has happened here. Villains or victims, we are all part of something much bigger than this trial. The working class movement cannot allow this verdict to go unchallenged.' DES WARREN speaking from the dock in December 1972. This defiant speech

appears in Ricky's autobiography, Ricky (Time Warner, £17.99). |